Ms. Shanika

At 16, Sarah was determined to leave Maryland to attend college in Florida. She spent a week touring campuses there with her Aunt Leslie and her mom during the spring of her junior year of high school.

Back then, Sarah had strong grades and participated in plenty of extracurricular activities. She ran track. She was an officer in her school’s Minority Scholars Program. She was a member of a student club for American Sign Language, which she uses to communicate with her oldest brother, who is deaf. She had every expectation of becoming the first person in her family to graduate from college.

Then she got pregnant. She gave birth just before Christmas, during winter break of her senior year. A few days before she went into labor, Sarah selected a name for her son: Noah. It reminded her of the biblical man whose story—the flood, the ark—represented forgiveness, and a fresh start. The day after Sarah chose the name, she saw a double-rainbow in the sky.

Noah’s arrival transformed Sarah. But her daily life didn’t slow down. About a week after Sarah gave birth, she had to take an exam for one of the online classes she had switched into late in her pregnancy. And in early February, she returned to high school in person. She breast-fed her son, to the extent that she could, for the next six months.

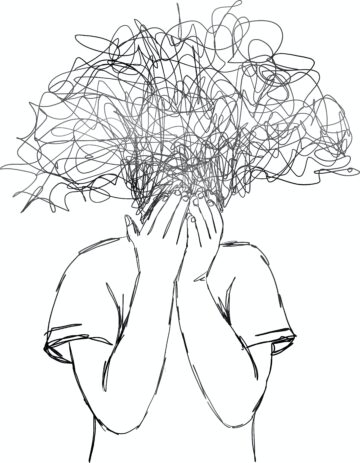

“It seemed impossible,” Sarah says. “I was so stressed out.”

As a new mom, Sarah reconsidered her higher education plans. She decided that she wanted to give Noah’s father an opportunity to build a relationship with his son. That seemed more likely if Sarah stayed in Maryland to attend college.

“I had to let Florida go,” she says.

On the counsel of a friend from her track team, Sarah enrolled at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. She now thinks it was a wise choice. She has appreciated how the smaller school has helped her make connections, and that it’s the kind of place where other students study in the library until 4 a.m.

“It’s motivating to be around other people who are equally as insane,” she says.

The university also has a whole community of students who live off campus and commute to class each day, so Sarah doesn’t feel like the only person left out of dorm culture, even if most of the others have different reasons for not staying in the residence halls.

It’s near the university’s commuter-student lounge that Sarah settles in at 11 a.m., time for her scheduled check-in with Shanika Hope.

Sarah calls her “Ms. Shanika.” She is Sarah’s mentor—one of many. They were paired together through Generation Hope, a nonprofit that provides coaching, tutoring, tuition money and other services to teen parents as they pursue higher education.

Such support is needed because research shows that women who give birth as teenagers are less likely than their peers to graduate from high school, and even less likely to graduate from college. Leaders at Generation Hope argue that this is in part because few colleges are set up to address the needs of students who are raising children, even though they make up a fifth of today’s undergraduates.

As a rising junior in college, Sarah signed up for Generation Hope to meet other young parents.

“It helps you know that you’re not alone. ’Cause sometimes I’m like, ‘Am I the only parent here?’ I feel really isolated,” Sarah says. “It’s like, ‘No, we’re doing it, we know it’s hard, and you have other people that are doing it with you.’”

Ms. Shanika, a mom of two teenagers who works at Google training engineers, signed up to mentor because of her memories of what her younger sister experienced when she had a child at age 18.

“I tried to help my sister stay the course to get her college degree, to have better outcomes. That didn’t happen,” Ms. Shanika says. “Fast-forward 23 years later, I just feel compelled to help enable other young mothers to stay the course.”

When she volunteered for Generation Hope, Ms. Shanika had girded herself to encounter a mother and child in desperate circumstances. About two-fifths of college students who are raising kids are single mothers, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research; most have low incomes, and many struggle to find enough time for their studies.

“I had the worst in mind, honestly,” Ms. Shanika says. “When the match happened and we had the initial conversation? Stunning. The first conversation, I was like, wait a minute, this young woman has got it together.”

Ms. Shanika marvels at Sarah’s poised personality, explaining that “Sarah is very forthright, very focused and has a clear understanding of her path.”

Yet Ms. Shanika also notes that her mentee has an unusually solid community surrounding her: “What’s unique is Sarah has a very strong support network, which enables her to fly.”

What difference does a network make? Financial resources count for a lot. So does child care. Sarah’s mom watches Noah three days a week this semester. Her father and one of her brothers live nearby and are there for her if she needs support—say, if she falls ill. Less tangible, but just as significant, Ms. Shanika says, is how support can instill a young woman with confidence and empower her to think, not just survive.

“Teen moms are dealing with shame, and it causes them to become insular. They lose the friend groups and support they originally had when they got pregnant,” Ms. Shanika says. In contrast, Sarah “has a natural curiosity that has not been closed off by being a teen mom. She makes space for it,” Ms. Shanika adds. “My sister and others that I’ve supported in similar constraints, it gets squelched because of all that they’re managing.”

Sensing all of Sarah’s potential, Ms. Shanika tries to act as a coach. Not for academics—Sarah gets high grades in her psychology courses—but for building more peace into her long days. The pair talk about how to get more than five hours of sleep, how to set aside time to spend with friends, how to take care of a child while also taking care of yourself.

Sarah squeezes time for herself into the 60 minutes between 8 to 9 p.m. It’s the first hour after Noah’s bedtime, when Sarah says she takes time to “eat, lay down and just breathe” before turning back to work for another three or four hours.

“Sarah leans with a ‘yes’ in her life. Helping her be comfortable saying ‘no’—we’ve spent a lot of time there,” Ms. Shanika says. “She’s not a people pleaser, but she’s so capable and she wants to help, so she just struggles with focusing on the essentials.”

That was clear during one of Sarah and Ms. Shanika’s early conversations soon after they were paired up, last semester during the fall of Sarah’s junior year of college. Sarah explained that she was creating flyers for four different campus events. She was in the middle of exams. Noah’s nose was running, and he had missed a week of school.

“Just make sure you are being kind to yourself,” Ms. Shanika counseled during the call. “Everything you’re describing, it’s a lot of responsibility. And your son is sick.”

They talked about remedies for a toddler’s cold, and the best brand of rubber pants to help with potty training. They talked about graduate school applications, and what life might feel like if Sarah relocates to continue her studies and no longer has family members nearby to watch Noah during the week.

“She’s young. Doubt comes. She’s balancing a lot,” Ms. Shanika says later. “I just get to ride along, give her additional nudges, give her confidence and calibrate as she makes decisions. She’s a unicorn, I would say. I literally am just tagging along with a little bit of superstar.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.edsurge.com/news/2022-12-15-the-many-mentors-of-sarah-turner

- 11

- 9

- a

- About

- According

- Act

- activities

- Additional

- address

- Adds

- After

- All

- alone

- American

- and

- Another

- applications

- argue

- around

- arrival

- attend

- back

- baltimore

- because

- become

- becoming

- before

- being

- BEST

- Better

- between

- Bit

- brand

- Break

- brothers

- build

- Building

- call

- Calls

- Campus

- capable

- care

- causes

- child

- Children

- choice

- Christmas

- circumstances

- class

- classes

- clear

- closed

- club

- coach

- coaching

- College

- Colleges

- comfortable

- communicate

- community

- Commute

- compelled

- confidence

- Connections

- constraints

- continue

- contrast

- Conversation

- conversations

- could

- counsel

- county

- course

- Creating

- Culture

- curiosity

- daily

- day

- Days

- dealing

- decided

- decisions

- Degree

- determined

- different

- Doesn’t

- doing

- dorm

- doubt

- down

- during

- each

- Early

- Education

- empower

- enable

- enables

- encounter

- Engineers

- enough

- enrolled

- equally

- essentials

- Even

- events

- exam

- expectation

- experienced

- explained

- explaining

- Fall

- Falls

- family

- family members

- few

- financial

- Find

- First

- florida

- focused

- focusing

- Forgiveness

- fresh

- friend

- friends

- from

- generation

- get

- Give

- Go

- graduate

- Group’s

- happen

- happened

- Hard

- help

- helped

- helping

- helps

- here

- High

- higher

- Higher education

- hope

- HOURS

- How

- How To

- HTTPS

- impossible

- in

- initial

- INSANE

- isolated

- IT

- kids

- Kind

- Know

- labor

- language

- Last

- Late

- leaders

- Leave

- Library

- Life

- likely

- little

- live

- Long

- longer

- lose

- Lot

- Lounge

- Low

- make

- MAKES

- man

- managing

- many

- Maryland

- Match

- Meet

- member

- Members

- Memories

- Middle

- might

- mind

- minutes

- mom

- money

- months

- more

- most

- mother

- MS

- name

- Natural

- Near

- needed

- needs

- network

- New

- next

- Noah

- Nonprofit

- nose

- Notes

- Officer

- oldest

- ONE

- online

- Opportunity

- originally

- Other

- Others

- paired

- parents

- part

- participated

- path

- People

- person

- Personality

- Place

- plans

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Plenty

- policy

- potential

- Pregnancy

- provides

- Psychology

- raising

- RE

- reasons

- relationship

- research

- Resources

- responsibility

- Ride

- rising

- rubber

- running

- scheduled

- Scholars

- School

- seemed

- selected

- Services

- set

- settles

- Shows

- sign

- signed

- significant

- similar

- single

- SIX

- Six months

- sleep

- slow

- smaller

- So

- solid

- son

- Soon

- Space

- spend

- spent

- spring

- start

- stay

- stayed

- strong

- Struggle

- Struggles

- Student

- Students

- studies

- Study

- Superstar

- support

- Supported

- Surrounding

- survive

- switched

- Take

- takes

- taking

- Talk

- team

- teen

- teenagers

- The

- their

- Thinks

- three

- Through

- time

- to

- today’s

- together

- touring

- track

- Training

- transformed

- Turning

- Tutoring

- understanding

- unicorn

- unique

- university

- University of Maryland

- wait

- wanted

- Watch

- watches

- week

- What

- which

- while

- WHO

- Winter

- WISE

- woman

- Women

- Work

- works

- Worst

- would

- year

- years

- young

- Younger

- Your

- yourself

- zephyrnet