Strawberries at Christmas: an image that epitomizes consumer fantasies from the global food supply chain. Hidden behind the haze of food supply “magic” is the reality of increasingly pressured resources relying on global flows of container shipping and air freight. A fraught and sometimes fragile system that brings us Chilean blueberries, Mexican avocados, Argentinian blackberries, sugar snap peas from Zambia and roses from Kenya.

Food retailers and consumers have become used to a settled landscape, a global network that has kept moving, based on predictable demand and familiarity when it comes to the direction of flows of goods. We’ve become confident that we’ll always find what we’re looking for on the store shelves.

The huge dislocation in food supplies

The biggest shock and the biggest lessons for food supply chains have obviously come from the COVID-19 pandemic. The global crisis resulted in a huge dislocation of the system and an ongoing legacy of disruption, displacement and uncertainty. The foundations of that settled picture of supply chains have been moved around or have fallen apart.

During the height of COVID-19, societies around the world were limited by lockdowns in their spending on foods, in restaurants and other food outlets. There was lower demand for foods combined with a decline in availability because of affected logistics and lack of staff. In turn, farms and producers were limiting their operations and cutting back on unnecessary costs. There were even campaigns to encourage people to eat crops that would otherwise go to waste — Belgians were encouraged to eat more fries to tackle the potato mountain.

Now, we’re experiencing the other end of the tsunami as the ocean of renewed demand rolls in, overwhelming the food supply system.

The latest figures for European imports of food suggest increases of more than 130 percent compared with December. Restaurants have opened up; events are taking place. Freed from distancing restrictions and curfews, people want to be out and spending money to make up for lost time.

Container shipping is out of sync and struggling to cope with renewed demands.

[node:field-gbz-pull-quote:0]

Pre-pandemic, the costs to send goods to China were almost nothing, because otherwise, firms were sending back empty containers, generating bizarre anomalies, such as how it would be cheaper for French mineral water to be sent to China rather than the short hop across the channel to the U.K.

But now, the extraordinary breaks in demand have meant containers are not following conventional flow patterns and not always returned to the locations where most goods have typically been produced. They are like supermarket trolleys scattered around the extremities of the car park.

We’re seeing spikes in container shipping prices due to renewed demand and messy distribution, particularly for the food sector and its need for specialist temperature-controlled containers.

Container costs between China and North America now average $17,970, up 1,250 percent. Prices are also up 850 percent from China to Northern Europe. Similarly, costs of air freight were kept to a reasonable level because goods were transported along with passengers — people up top, goods below. Costs rocketed while flights were limited, and they continue to be affected by the slow return to more “normal” levels of travel.

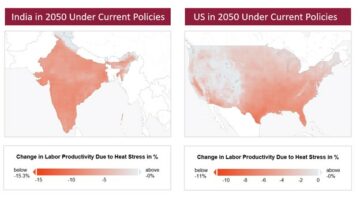

Climate change will create further disruption

Climate change and the more regular occurrence of extreme weather events are going to disrupt this kind of stability, as a matter of course, in terms of ruined crops, water supplies and impact on livestock. A Chatham House report suggests yields of staple food crops will decline by almost a third by 2050. This year, for example, there have been lower yields of coffee beans, meaning higher prices and lower-quality products are coming.

The world’s largest producers of durum wheat, Canadian farmers, saw their usual yields reduced by half this year and pasta prices are expected to rise steeply. More farmers and other producers will be looking to focus their business around where they can find the greatest financial security, shifting to more resilient foodstuffs, meaning some types of produce will become scarce, and some regions will potentially move away from agriculture entirely.

What does a better food supply chain look like?

We’re heading from a “pre-new normal” stage into a “new normal,” or what should most constructively be seen as a “new better.”

There are obvious lessons from the demand tsunami that can help members of the food supply chain internationally to focus on resilience and adaptability. The challenge is making the transition and navigating the ways in which the necessary changes to the system will affect everyone, meaning new attitudes and approaches in producers, manufacturers, distributors and consumers.

Lower transport costs, smaller carbon footprint, fewer touch points, more control. But just because a country wants to onshore, of course, doesn’t mean it can. There will be difficult issues around infrastructure, skills, labor and know-how, as well as climate and soils. Where there is strong market demand and investment for localized food production, ingenuity and innovation will follow.

Touchless agriculture is on the horizon

The food sector will need to think cleverly to find ways to minimize waste in logistics, to get more from every food mile. For example in Australia, that might mean a product such as wine is transported in large boxes for local bottling. More distributed manufacturing rather than large factories; more 3D printed food. Smarter collaborations between businesses and across sectors to share the best use of logistics operations.

New technologies being trialed mean a “touchless” agriculture from farm to fork — foods planted, monitored and picked via AI and robotics — is on the horizon.

Any radical new model of food supplies has to be based on holistic decision-making. As societies, we can’t keep insisting on, and benefiting from, supply chains structured solely around issues of efficiency and cost. There needs to be attention to the trade-offs between planet and people.

We can easily stop buying roses from Kenya, but that will mean lost jobs and livelihoods. Sustainability in the system doesn’t only mean net zero carbon dioxide, but what is workable in terms of the bigger social context. We can live with fewer food choices, but not without jobs. The poverty created by the collapse of food-related economies is only ever likely to lead to more production and supply disruption as a result of extremism and civil unrest.

Building resilience as consumers

For consumers to want to contribute toward sustainability and security, we need to be more resilient as consumers. That means learning to be more realistic about seasonal availability.

Do we really need strawberries and asparagus at Christmas in the northern hemisphere?

If we do, then we should expect them to come with a heavy price tag to reflect supply chain truths. And we need to become used to having fewer choices, just six types of pasta rather than the usual 20. Fewer exotic, specialized food treats.

The greatest risk to this post-pandemic, climate-conscious world would be for consumers to expect a return to the old normal, to fall back into old habits. The spiral toward more supply chain fragility and supply shocks would only intensify again.

Source: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/global-food-supply-chains-are-being-overwhelmed