WASHINGTON — The Intuitive Machines Nova-C lunar lander likely tipped over when touching down on the moon Feb. 22 and is now resting on its side.

In a televised media teleconference Feb. 23, nearly 24 hours after the IM-1 mission landed on the moon, company officials said they believed the lander, 4.3 meters tall and 1.6 meters in diameter, is resting on its side a few kilometers from its intended landing site near the Malapert A crater in the south polar regions of the moon.

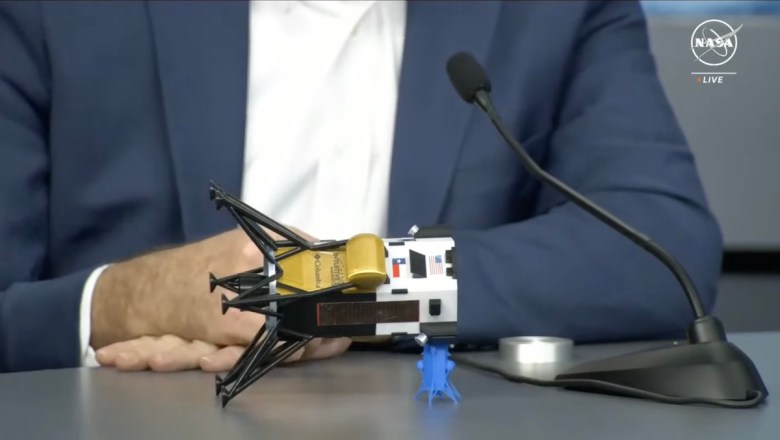

The lander “caught a foot in the surface, and the lander has tipped,” said Steve Altemus, chief executive of Intuitive Machines, illustrating the status of the lander with a small model of it.

He suggested that was caused by the lander coming down faster than expected. The lander’s final descent was supposed to be straight down at about one meter per second, but was instead descending at about three times that velocity with about one meter per second of lateral motion.

“If you catch a foot, we might have fractured that landing gear and tipped over gently,” he said. The lander appears to be resting on a rock, elevating it slightly above the surface, based on the power it is generating; he said the foot could also be in a crevice.

Intuitive Machines had reported a couple hours after the landing that the lander was upright. However, Altemus said that determination was based on “stale telemetry” from fuel tanks on the lander.

The lander has yet to return images as controllers work to reconfigure radios on the spacecraft. Tim Crain, chief technology officer of Intuitive Machines, said they are still determining what data rates they can get with the lander on its side and some antennas thus not usable. “We expect to get most of the mission data down once we stabilize our configuration,” he said.

Fortunately, the only payload mounted on the side of the lander now facing the surface is a static payload: an artwork provided by artist Jeff Koons. Other commercial and NASA payloads are operating, and many of them collected data during the flight to the moon and during the descent to the surface.

One of those NASA payloads may have saved the mission. Engineers were able to use data from the Navigation Doppler Lidar instrument developed at NASA’s Langley Research Center to replace laser rangefinders on the lander that were not working.

Controllers discovered the problem with the lander’s laser rangefinders after going into orbit around the moon Feb. 21 and deciding to use them to more precisely measure the lander’s orbit, which was more elliptical than intended. The lasers, though, did not work, and engineers determined that a physical switch — a safety measure on the ground because the lasers are not eye-safe — was not flipped before launch.

“It was like a punch in the stomach. We were going to lose the mission,” Altemus recalled. Crain then found it would be possible to take the data from two lasers in the NASA instrument and incorporate them into the lander’s navigation system.

“In normal software development for a spacecraft, this is the kind of thing that would have taken a month,” Crain said. “Our team basically did that in an hour and a half.”

That process also provided a greater validation of the NASA payload than originally expected. “The technology performed flawlessly,” said Prasun Desai, NASA deputy associate administrator for space technology. “It acquired range and velocity data well above the required five-kilometer altitude as it was descending.”

He noted the goal of flying the payload was to achieve a technology readiness level (TRL) of 6 on a 1-to-9 scale, validating a prototype of the technology in a relevant environment. With its use on the landing, “we were able to get an operational system now, TRL 9. It’s ready to be used from now on.”

Altemus added it was “fortuitous” that Nova-C was in an elliptical orbit that prompted engineers to activate the laser rangefinder earlier than expected and thus discovered the problem. “That was fortunate and a bit of luck for us.”

In normal operations, Crain said, the laser rangefinders would not have been activated until after the lander began its powered descent to the surface. “We would have probably been five minutes to landing before we realized those lasers weren’t working,” he said.

One payload yet to operate is EagleCam, a student-built camera that was designed to eject from the lander about 30 meters from the surface and take images of the landing. However, the ejection did not take place after the software on the lander was revised to make use of the Navigation Doppler Lidar data. Altemus said EagleCam is mounted on a side panel and should be able to eject later in the mission, which may last 9 to 10 days on the surface, providing images of the lander.

Crain said the lander is likely within two to three kilometers of the planned landing site, based on the performance of optical navigation sensors on the lander. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter is scheduled to pass over the landing area in the next few days and will take images in an effort to pinpoint the landing location.

Despite the lander being on its side, both the company and NASA played up the milestones of the mission. That included being the first commercial spacecraft to land softly on the moon, the first American spacecraft to do so since Apollo 17 in December 1972 and the mission to land the closest yet to the lunar south pole, at a latitude of about 80 degrees south.

The landing was a validation of NASA’s approach, through its Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, of having companies design, build and operate lunar lander missions, argued Joel Kearns, deputy associate administrator for exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “This is a gigantic accomplishment.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spacenews.com/im-1-lunar-lander-tipped-over-on-its-side/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- $UP

- 1

- 10

- 17

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 30

- 4

- 6

- 80

- 9

- a

- Able

- About

- above

- Achieve

- acquired

- activate

- activated

- added

- After

- also

- American

- an

- and

- apollo

- appears

- approach

- ARE

- AREA

- argued

- around

- artist

- artwork

- AS

- Associate

- At

- based

- Basically

- BE

- because

- been

- before

- began

- being

- believed

- Bit

- both

- build

- but

- by

- camera

- CAN

- Can Get

- Catch

- caused

- Center

- chief

- Chief Executive

- chief technology officer

- closest

- collected

- coming

- commercial

- Companies

- company

- Configuration

- could

- Couple

- crain

- credit

- data

- Days

- December

- Deciding

- deputy

- Design

- designed

- determination

- determined

- determining

- developed

- Development

- DID

- discovered

- do

- down

- during

- Earlier

- effort

- ejection

- elevating

- Engineers

- Environment

- executive

- expect

- expected

- exploration

- facing

- faster

- Feb

- few

- final

- First

- five

- flight

- flying

- Foot

- For

- fortunate

- found

- from

- Fuel

- Gear

- generating

- get

- goal

- going

- greater

- Ground

- had

- Half

- Have

- having

- he

- hour

- HOURS

- However

- HTTPS

- illustrating

- images

- in

- included

- incorporate

- instead

- instrument

- intended

- into

- intuitive

- IT

- ITS

- jpg

- kilometers

- Kind

- Land

- landing

- laser

- lasers

- Last

- later

- latitude

- launch

- Level

- lidar

- like

- likely

- location

- lose

- luck

- Lunar

- lunar lander

- Machines

- make

- many

- max-width

- May..

- measure

- Media

- might

- Milestones

- minutes

- Mission

- missions

- model

- Month

- Moon

- more

- most

- motion

- Nasa

- Navigation

- Near

- next

- normal

- noted

- now

- of

- Officer

- officials

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- operate

- operating

- operational

- Operations

- optical

- Orbit

- originally

- Other

- our

- over

- panel

- pass

- per

- performance

- performed

- physical

- Place

- planned

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- played

- polar

- possible

- power

- powered

- precisely

- probably

- Problem

- process

- Program

- prototype

- provided

- providing

- punch

- range

- Rates

- Readiness

- ready

- realized

- regions

- relevant

- replace

- Reported

- required

- research

- resting

- return

- Rock

- Safety

- Said

- saved

- Scale

- scheduled

- Science

- Second

- sensors

- Services

- should

- showing

- side

- since

- site

- slightly

- small

- So

- Software

- software development

- some

- South

- Space

- spacecraft

- stabilize

- static

- Status

- Steve

- Still

- straight

- supposed

- Surface

- Switch

- system

- Take

- taken

- Tanks

- team

- Technology

- televised

- than

- that

- The

- Them

- then

- they

- thing

- this

- those

- though?

- three

- Through

- Thus

- Tim

- times

- to

- touching

- two

- until

- Upright

- us

- usable

- use

- used

- validating

- validation

- VeloCity

- was

- we

- WELL

- were

- What

- when

- which

- will

- with

- within

- Work

- working

- would

- yet

- you

- zephyrnet