[This post has been authored by SpicyIP Intern Kevin Preji. Kevin is a second-year law student at NLSIU Bangalore. His passion lies in understanding the intersection of economics and public health with intellectual property rights. His previous posts can be accessed here.]

In the case of Sterling Agro Industries Limited vs ASR Trading Company, the Delhi High Court while dealing with a trademark infringement suit, imputed mala fide intention to ASR Trading’s (the Defendant) act of applying for a trademark registration. The impugned mark in question was “Novya” which was alleged to be similar to Sterling Agro’s (the Plaintiff) “Nova” mark. Given that trademark infringement suits over deceptively similar trademarks occur all the time, this post attempts to highlight when bad faith can be imputed to the act of registering a deceptively similar trademark.

Facts of the Case

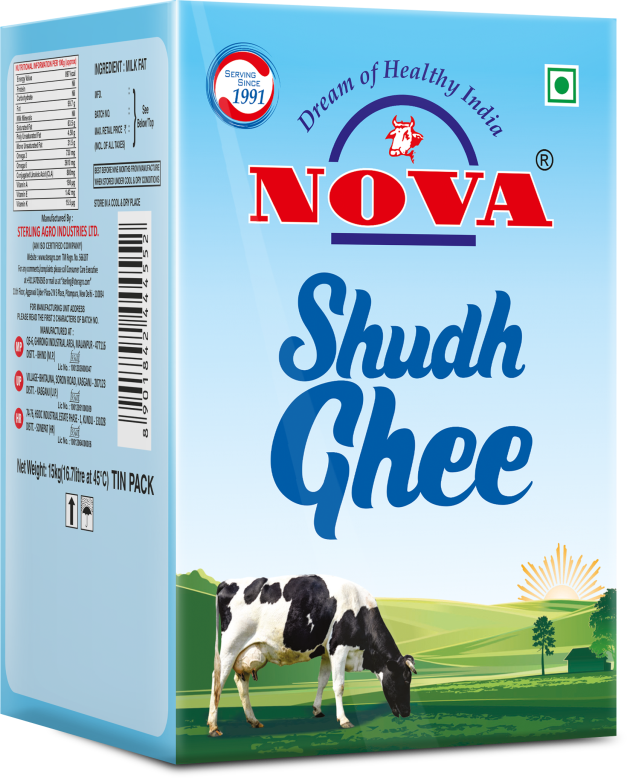

In this case, the Plaintiff, an incorporated company engaged in the manufacturing of dairy products under the trademark ‘NOVA,’ filed a suit against the Defendants for infringement and passing off of their registered trademark. The Plaintiff alleged that the Defendants, a partnership firm, were using the deceptively similar mark ‘NOVYA’ for identical goods, specifically Ghee, and imitating the Plaintiff’s packaging. The Plaintiff presented evidence of its long-standing use and registration of the ‘NOVA’ trademark, along with the distinct packaging featuring a blue background, a grazing cow, and the brand name.

The Court granted an interim injunction in favour of the Plaintiff and appointed a Local Commissioner to inspect the Defendants’ premises, resulting in the recovery of an empty box of the contested product. In their written statement, the Defendants claimed distinctions between the marks and denied any unlawful activities, asserting that their trademark application for ‘NOVYA’ covered a broader range of goods, and commercial activities had not yet commenced.

During the proceedings, the Court observed and penalised the Defendants for false advertising and contemptuous conduct. The Defendants’ inconsistent representation and sporadic appearance in court indicated a disregard for legal obligations. The court rejected the Defendants’ defence of dissimilarity between the marks, finding a clear case of infringement due to visual and phonetic similarities. The Defendants’ application to register the trademark ‘NOVYA’ during the existence of the Plaintiff’s registered mark suggested a deliberate attempt to capitalise on the Plaintiff’s goodwill.

The Court decreed the suit in favour of the Plaintiff, granting a permanent injunction and awarding litigation costs. Additionally, the Defendant was held guilty of contempt, and a penalty of INR 5 Lakhs was imposed. The court emphasised the Defendants’ bad faith and their attempt to mislead consumers by imitating the Plaintiff’s trademark and packaging.

Mala fide intention or Merely Coincidence?

The Court determined that the Defendants’ submission of a trademark application for the ‘NOVYA’ mark, while the Plaintiff’s ‘NOVA’ trademark was already validly registered, not only showed a lack of respect for the Plaintiff’s established trademark rights but also implied a deliberate effort to benefit from the Plaintiff’s goodwill. One might wonder how such an implication came about especially since trademark infringement suits over deceptively similar trademarks arise all the time. The act of applying to register the trademark ‘NOVYA’ could also imply a genuine belief that either the trademark ‘NOVA’ was not similar to the trademark ‘NOVYA’ or there existed no other deceptively similar trademark in the market. After all, the Registrar wouldn’t allow the registration of a trademark if a deceptively similar trademark exists under Section 11 of the Trademark Act, 1999. (Additionally, under Section 11(10) of the Trademark Act, the Registrar would take into consideration ‘Bad Faith’ on part of the applicant or the opposition in the application process) If there exists multiple safeguards to prevent deceptively similar trademarks or trademarks registered in bad faith within the application process itself, what factors does the Court rely on to impute Bad Faith to the act of registering the trademark? The next section explores the various factors that courts rely on to impute bad faith.

How then does the Court Impute Bad Faith in Such Cases?

A case that has often been cited in many orders by the Indian courts (see here, here and here) in this regard is the English and Wales High Court decision in Gromax Plasticulture Ltd v. Don & Low Nonwovens. The English Court defined bad faith as the element of dishonesty in some dealings which fall short of the standards of acceptable commercial behaviour deserved by reasonable and experienced men in the particular area being examined. In Bhupinder Singh v. State of Rajasthan, the Court clarified bad faith to be different from a bad judgement or negligence, emphasising on the element of dishonesty and conscious wrongdoing. (Although this judgement wasn’t originally related to trademark law, this understanding of bad faith has been frequently cited in recent trademark judgements).

Courts usually look at multiple factors to determine whether the defendant had the intention to ride on the goodwill of the plaintiffs. One of the major factors being possession of the knowledge of the plaintiff’s trademark (regardless of whether it’s registered or not) before the filing of the trademark application. (This article argues for this factor in reference to ‘well-known marks’ regardless of registration). The Delhi High Court in Kia Wang vs The Registrar Of Trademarks extends this even beyond well-known marks by stating that since it was unfathomable that the defendant’s were unaware of the plaintiff’s trademark, the defendants had adopted the same only to ride upon the goodwill and reputation of the petitioner. (Here, the plaintiff’s trademark wasn’t considered to be a well known trademark as defined under Section 2(1)(zg) of the 1999 Act). While one might assume that bad faith arises only when an applicant deliberately provides inaccurate or insufficient information to the Office, it is also imputed when the intention is to register a trademark belonging to a third party with whom the applicant had contractual or pre-contractual dealings.

In BPI Sports LLC vs Saurabh Gulati, the court listed a few instances (in reference to website domains) where bad faith could be imputed, namely –

- Acquiring trademark registration for the purpose of selling/renting or transferring registration

- Registering trademark to prevent owner of trade mark from usage

- Registering trademark to primarily prevent or disrupt the business of a competitor

- Registering a trademark to create a likelihood of confusion with the complainant’s mark as to source, sponsorship, affiliation or endorsement.

Conduct of the Defendants

A close look at the Defendant’s actions clearly highlights the bad faith to ride on the hard earned goodwill of the Plaintiff. The Court highlighted that the trademarks “NOVA” and “NOVYA” are clearly deceptively similar. This is compounded by the fact that the Defendants were aware of the Plaintiff’s reputation in the Milk and Ghee industry, thus adapting a deceptively similar trade dress. It is evidently clear at this point that the intention was to pass off their goods as the goods of the Plaintiff’s and rely on their reputation. While the Defendants had filed the trademark registration application, the Court pointed out the subsequent abandonment of the Defendants’ trademark application after opposition by the Plaintiffs, concluding that their adoption of the contested mark was conducted with dishonest and mala fide intentions. Finally, the disregard to appear for the hearings, inconsistencies within the written statements and statements recorded before the Court and the misleading advertising stating that the Defendants possessed a “Government of India Registered Trademark” despite abandoning the trademark application played a role in imputing bad faith to the actions of the Defendants.

The Court appropriately went the extra mile to impute bad faith to the infringer’s activities. This is because holding the Defendants in contempt and imposing a penalty, as opposed to just an injunction and a suit for damages, serves to increase the costs borne by the Defendants. Additionally, it acts as a deterring factor for infringers and safeguards the integrity of the Court. This is particularly important given the sporadic appearances of the defendants before the Court and their disregard for the Plaintiff’s trademark rights.

Conclusion

In trademark infringement suits, often parties file for registration with genuine belief in the lack of deceptive similarity between the contested trademarks. Nevertheless, multiple factors help courts determine whether bad faith can be imputed to the Defendant’s actions such as prior knowledge of the trademark, identical or similar trade dress, deceptively similar trademark with a trademark that isn’t allegedly descriptive, etc. The Court rightly penalised the Defendants with a hefty sum of 5 Lakhs for their mala fide act of infringing the trademark of the Plaintiff.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/03/imputing-bad-faith-in-trademark-infringement-disputes-analysing-dhc-nova-v-novya-judgement.html

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- 1

- 10

- 1999

- 5

- a

- Abandonment

- About

- acceptable

- accessed

- Act

- actions

- activities

- acts

- adapting

- Additionally

- adopted

- Adoption

- Advertising

- After

- against

- All

- alleged

- allegedly

- allow

- along

- already

- also

- Although

- an

- analysing

- and

- any

- appear

- appearances

- Application

- Applying

- appointed

- appropriately

- ARE

- AREA

- Argues

- arise

- arises

- AS

- Asserting

- assume

- At

- attempt

- Attempts

- authored

- aware

- background

- Bad

- BE

- because

- been

- before

- behaviour

- being

- belief

- belonging

- benefit

- between

- Beyond

- Blue

- Box

- brand

- broader

- business

- but

- by

- came

- CAN

- case

- cases

- cited

- claimed

- clarified

- clear

- clearly

- Close

- coincidence

- commenced

- commercial

- commissioner

- company

- compounded

- concluding

- Conduct

- conducted

- confusion

- conscious

- consideration

- considered

- Consumers

- contractual

- Costs

- could

- Court

- Courts

- covered

- cow

- create

- dairy

- dealing

- decision

- decreed

- defence

- defendants

- defined

- Delhi

- denied

- depicting

- Despite

- Determine

- determined

- different

- dishonest

- disputes

- Disrupt

- distinct

- does

- domains

- don

- due

- during

- earned

- Economics

- effort

- either

- element

- emphasised

- emphasising

- empty

- Endorsement..

- engaged

- English

- especially

- established

- etc

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- evidence

- existed

- existence

- exists

- experienced

- explores

- extends

- extra

- fact

- factor

- factors

- faith

- Fall

- false

- Featuring

- few

- File

- filed

- Filing

- Finally

- finding

- Firm

- For

- frequently

- from

- genuine

- given

- goods

- Goodwill

- granted

- granting

- guilty

- had

- Hard

- Health

- hefty

- Held

- help

- here

- High

- Highlight

- Highlighted

- highlights

- his

- holding

- How

- HTML

- HTTPS

- identical

- if

- image

- implied

- imply

- important

- imposed

- imposing

- in

- inaccurate

- inconsistencies

- inconsistent

- Incorporated

- Increase

- india

- Indian

- indicated

- industries

- industry

- information

- infringement

- instances

- insufficient

- integrity

- intellectual

- intellectual property

- Intention

- intentions

- interim

- intersection

- into

- IT

- ITS

- itself

- just

- knowledge

- known

- Lack

- Law

- Legal

- lies

- likelihood

- Limited

- Listed

- Litigation

- LLC

- local

- long-standing

- Look

- Low

- Ltd

- major

- manufacturing

- many

- mark

- Market

- max-width

- Men

- merely

- might

- mile

- Milk

- misleading

- multiple

- name

- namely

- Nevertheless

- next

- no

- obligations

- observed

- occur

- of

- off

- Office

- often

- on

- ONE

- only

- opposed

- opposition

- or

- orders

- originally

- Other

- out

- over

- owner

- packaging

- part

- particular

- particularly

- parties

- Partnership

- party

- pass

- Passing

- passion

- permanent

- phonetic

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- played

- Point

- possession

- Post

- Posts

- presented

- prevent

- previous

- primarily

- Prior

- Proceedings

- process

- Product

- Products

- property

- Property Rights

- provides

- public

- public health

- purpose

- question

- range

- reasonable

- recent

- recorded

- recovery

- reference

- regard

- Regardless

- register

- registered

- registering

- registrar

- Registration

- Rejected..

- related

- rely

- representation

- reputation

- respect

- resulting

- Ride

- rights

- Role

- safeguards

- same

- Section

- see

- serves

- Short

- showed

- similar

- similarities

- since

- some

- Source

- specifically

- sponsorship

- sporadic

- Sports

- standards

- State

- Statement

- statements

- stating

- sterling

- Student

- submission

- subsequent

- such

- Suit

- suits

- sum

- Take

- that

- The

- their

- then

- There.

- Third

- this

- Thus

- time

- to

- trade

- trademark

- trademark application

- trademarks

- Trading

- Transferring

- unaware

- under

- understanding

- unlawful

- upon

- use

- using

- usually

- various

- visual

- vs

- wang

- was

- Website

- WELL

- well-known

- went

- were

- What

- when

- whether

- which

- while

- whom

- with

- within

- wonder

- would

- written

- yet

- zephyrnet