In light of the recent controversy concerning a Delhi-based restaurant’s use of a “Michelin plaque”, we are pleased to bring to you this guest post by Dr. (Prof.) Sunanda Bharti on the Michelin Stars and its interaction was trademark laws. Prof. Bharti is a Professor of Law at Delhi University, and her previous posts can be accessed here.

Mischief, Manifestation, and the Michelin Trademark!

By Dr. (Prof.) Sunanda Bharti

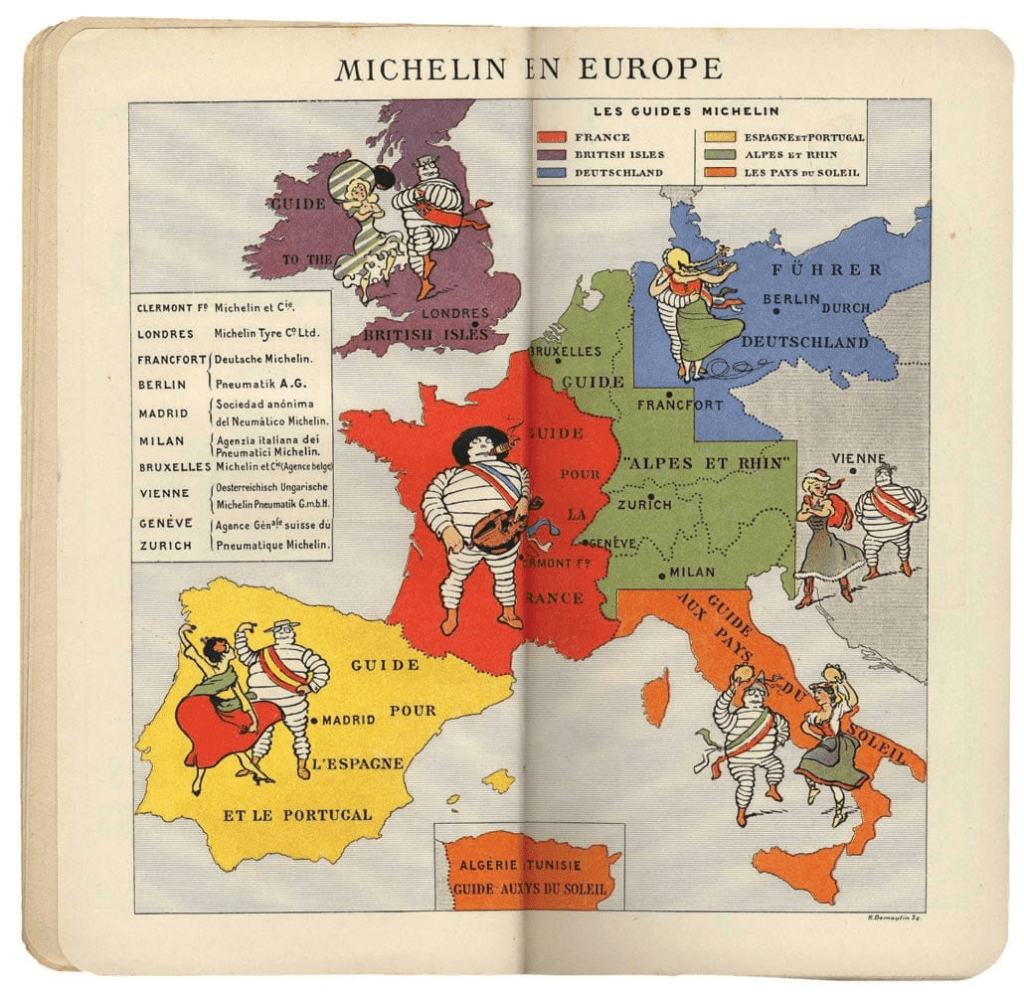

Vir Sanghvi, a prominent Indian journalist and author known for his insightful commentary on politics, society, and culture, recently confronted a Delhi restaurant manager regarding the display of a Michelin plaque at the establishment (see image 1), despite there being no Michelin guide for India and thus, no awarded distinctions such as stars or Bib Gourmand ratings etc. The concerned Delhi-based restaurant used the Michelin plaque, carrying the Michelin word mark and the Michelin Bibendum device mark. Also, the plaque carried a fork, knife, and plate symbol (see also image 2) which was introduced by Michelin in the 2016 edition of the Paris Michelin Guide, as a brand new L’assiette’ or The Plate symbol to recognise restaurants that ‘simply serve good food’. The Michelin Plate is awarded to restaurants that are acknowledged for their quality, though they may still be working towards the ultimate goal of earning Michelin stars. So, in a way, it can be considered a precursor to earning a Michelin Star. In the instant case, though the Michelin Star mark was not specifically used— the Michelin Plate makes it clear that the intended reference is towards the restaurant being Michelin-approved or recommended) leading unaware customers to believe that the service is somehow Michelin-compliant or is likely to be in the future. In reality, however, the restaurateur in question is not a Michelin awardee.

Sanghvi questioned how the restaurant could have obtained such a plaque, implying that it misrepresented itself as a Michelin-recognised establishment. The manager defensively referred to the plaque as a ‘manifestation’ since the plaque referenced ‘Michelin 2025,’ implying an upcoming Michelin award!

As an IP enthusiast, the author perceives this as a trademark matter. Should the seemingly fraudulent behavior be taken in jest or be considered as a blatant misuse of the Michelin trademark— word and symbol? And more importantly, what kind of mark is a Michelin Star, which was the ultimate goal of this ‘manifestation’ attempt? The present post is devoted to this latter question.

Let’s deal with a bit of history first—Somewhere in 1900s, long before the era of the Internet, Michelin introduced the Michelin Guide, in France to aid motorists in planning their trips. It aimed to be a trusted source for diners as it offered insights into the finest restaurants and eating joints available in France. It has since become renowned ‘as an essential reference for gastronomy and the hotel trade’. Besides, it’s ‘Michelin Stars’ recognition, given to restaurants, has become a symbol of top-quality cooking and dining. For those unfamiliar, a Michelin star is awarded to restaurants showcasing exceptional cooking, evaluated on five criteria: 1) ingredient quality, 2) flavor harmony, 3) cooking technique mastery, 4) chef’s personality reflected in cuisine, and 5) consistency across the menu and over time.

While the Michelin Guide has expanded globally to over 40 destinations, India is notably excluded. Its expert and famously secretive food inspectors continuously update recommendations. This essentially means that the recognition in the form of Michelin Stars may be taken away, in case the quality deteriorates. It is relevant to underscore here that since there is no ‘Indian’ Michelin guide, there is no question of any Michelin recognition being awarded to any restaurant in India. The Delhi-based restaurant’s wrongful display of the ‘Michelin plate’ plaque misrepresents its status to the public.

What is a Michelin Star in Terms of Intellectual Property Law?

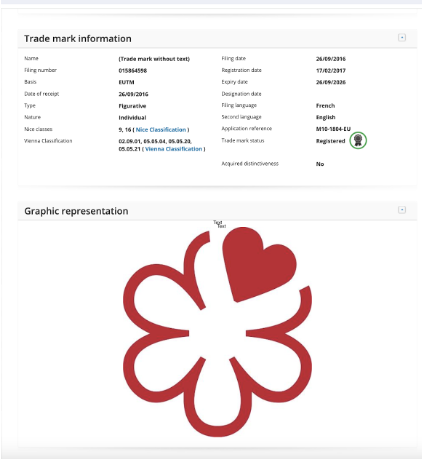

It is a registered trademark in the EU, under class 9 (includes mainly apparatus and instruments for scientific or research purposes, audiovisual and information technology equipment, as well as safety and life-saving equipment) and 16 (includes mainly paper, cardboard and certain goods made of those materials, as well as office requisites) since 2017 (see image 3 below). Its unauthorised use, hence, may be considered as infringement, where it is registered. Since the Indian Trademark Registry website is inaccessible because of ‘scheduled maintenance activity’, the author couldn’t verify the registration status of ‘Michelin Star’ in India. However, a passing-off claim could certainly be maintained against the concerned restaurateur, given the facts. Further, since ‘Michelin’ is a registered trademark under various classes (see trademark application number 3308763 which states that the ™ Michelin of France is registered by Compagnie Generale Des Etablissements Michelin in India under multiple classes: 35, 37, 39, 41, and 42), its unauthorized use may invite an infringement action.

However, a more curious aspect of the Michelin Star trademark is that it ends up operating as a certification trademark of sorts in the EU. It is not registered as such though. (It is relevant to note that the author had in a previous post similarly asserted that the Indian ‘Make in India’ mark acts more like a certification trademark). Let’s understand the notion of certification marks in the European Union (EU) regime (in India the concept is similar).

Article 83 of European Union Trademark Law (EUTM) deals with EU certification marks and states that an EU certification mark is a trade mark which is capable of distinguishing goods or services which are certified by the proprietor of the mark (in respect of material, mode of manufacture of goods or performance of services, quality, accuracy or other characteristics), from those of the others.

Any natural or legal person may apply to register their mark as a certification mark, provided that such person does not carry on a business involving the supply of goods or services of the kind certified. Also, the application should mention that it is for a ‘certification’ trademark.

Further, Article 84 of the EUTM law mentions the regulations governing the use of an EU certification mark and states that –

- Persons authorized to use the mark shall be specified;

- The characteristics to be certified by the mark must be mentioned; and

- How the certifying body is to test those characteristics and to supervise the conditions for the use of the mark, including sanctions must also be specified.

Barring the last requirement, the Michelin Star trademark ends up performing all functions of a Certification Mark.

To elaborate, Michelin-starred restaurants are considered different than (read a notch above) the rest. Michelin as such has been selling tyres and car accessories etc, but has never been into hospitality services itself. Lastly, not only does Michelin specify the conditions for the grant of Michelin Stars, but it supervises adherence to those conditions quite assiduously through its discreet, and often anonymous food inspectors.

And that is not all, the flower-shaped stars, so granted (whether one, two or maximum three) can be taken away ‘if we feel the cooking at a restaurant is no longer at the same level that it was’. So there are sanctions as well!

Conclusion

The discussion above highlights the unique nature and impact of any form of Michelin recognition and more so of Michelin Stars. Just as in the case of certification trademarks, the Michelin Star mark or any reasonable allusion to it (as in the present case), if used by a person who is not authorized to use the same, (as it does not fulfill the conditions for its use), should of course be considered as infringement.

Additionally, the author wonders that since a Michelin recognition (Plate, Star, Bib Gourmand) falls somewhat outside traditional trademark classifications and dwells more in the domain of certification trademarks—should the concern over its unauthorized use not be a bit more unsettling-IP wise? After all, though technically not a typical certification mark, any form of Michelin recognition and particularly the Michelin Star serves a similar function by indicating that restaurants that meet specific standards of culinary excellence established by the Michelin Guide, give a different quality cuisine and overall experience.

Strangely, however, the law in relation to certification trademarks is almost the opposite. To begin with, the conditions for infringement of a certification trademark, as outlined in Section 75 of the Trademarks Act 1999, are not as elaborate as Section 29 –which is for ordinary trademarks. In essence, section 75 simply says that infringement occurs when:-

- someone other than the registered owner or an authorized user uses the certification mark in the course of trade, or

- if a similar mark is used in connection with the goods or services that are the same as certified by the certification mark.

Also, section 135(3) of the Act states that the relief of damages in a suit for infringement and passing off of a Certification Trade Mark, awarded by a court, can only be ‘nominal’. Furthermore, there is a disappointing absence of case law on this matter, leaving room for interpretation and potential legal challenges.

Some solace is provided by the recent (2022) ruling, albeit foreign, by the Stuttgart Higher Regional Court, (which is the only case involving the infringement of an EU certification mark and found advertising to be an infringement of a certification mark), by underscoring the significance of such marks in protecting against misuse. So, had there been litigation in India and if Michelin Plate or Michelin Star were registered as certification marks, whether the ‘mischievous, manifestation attempt’ of use of the Michelin Plaque by the Delhi restaurant would likely have faced similar legal scrutiny, is a question that remains. It is compounded by lack of case-law guidance and seemingly relaxed legal provisions on certification marks in India (as mentioned above).

Overall, the author feels that the episode invites valuable reflection on trademarks that serve dual purposes beyond the traditional functions of a typical trademark.

All feedback here is welcome.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/03/mischief-manifestation-and-the-michelin-trademark.html

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 1

- 16

- 1999

- 2%

- 2016

- 2017

- 2022

- 2025

- 29

- 35%

- 39

- 4

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 5

- 75

- 84

- 9

- a

- above

- absence

- accessories

- accuracy

- acknowledged

- across

- Act

- Action

- acts

- adherence

- Advertising

- After

- against

- Aid

- aimed

- albeit

- All

- almost

- also

- an

- and

- Anonymous

- any

- Application

- Apply

- ARE

- AS

- aspect

- At

- attempt

- author

- authorized

- available

- awarded

- away

- BE

- because

- become

- been

- before

- begin

- behavior

- being

- believe

- below

- besides

- Beyond

- Bit

- body

- brand

- Brand New

- bring

- business

- but

- by

- CAN

- capable

- car

- carried

- carry

- Carry On

- carrying

- case

- certain

- certainly

- Certification

- Certified

- challenges

- characteristics

- claim

- class

- classes

- clear

- Commentary

- compounded

- concept

- Concern

- concerned

- concerning

- conditions

- connection

- considered

- consistency

- continuously

- controversy

- cooking

- could

- course

- Court

- criteria

- curious

- Customers

- deal

- Deals

- Delhi

- Despite

- destinations

- details

- device

- different

- diners

- dining

- disappointing

- discussion

- Display

- does

- domain

- dr

- dual

- Earning

- edition

- Elaborate

- ends

- enthusiast

- episode

- equipment

- Era

- essence

- essential

- essentially

- established

- establishment

- etc

- Ether (ETH)

- EU

- Europa

- Europe

- European

- european union

- European Union (EU)

- evaluated

- Excellence

- exceptional

- excluded

- expanded

- experience

- expert

- faced

- facts

- Falls

- famously

- feedback

- feel

- feels

- five

- flavor

- food

- For

- foreign

- fork

- form

- found

- France

- fraudulent

- from

- Fulfill

- function

- functions

- further

- Furthermore

- future

- Give

- given

- Globally

- goal

- good

- goods

- governing

- grant

- granted

- Guest

- Guest Post

- guidance

- guide

- had

- Harmony

- Have

- hence

- her

- here

- higher

- highlights

- his

- history

- hospitality

- How

- However

- HTML

- HTTPS

- if

- image

- Impact

- importantly

- in

- inaccessible

- includes

- Including

- india

- Indian

- indicating

- information

- information technology

- infringement

- ingredient

- insightful

- insights

- instant

- instruments

- intellectual

- intellectual property

- intended

- interaction

- Internet

- interpretation

- into

- introduced

- invite

- invites

- involving

- IP

- IT

- ITS

- itself

- journalist

- just

- Kind

- known

- Lack

- Last

- lastly

- latter

- Law

- Laws

- leading

- leaving

- Legal

- Level

- light

- like

- likely

- Litigation

- Long

- longer

- made

- mainly

- maintained

- maintenance

- MAKES

- manager

- map

- mark

- material

- materials

- Matter

- max-width

- maximum

- May..

- means

- Meet

- mention

- mentioned

- mentions

- Menu

- mischief

- misuse

- Mode

- more

- multiple

- must

- Natural

- Nature

- never

- New

- no

- notably

- note

- Notion

- number

- obtained

- of

- off

- offered

- Office

- often

- on

- ONE

- only

- operating

- opposite

- or

- ordinary

- Other

- Others

- outlined

- outside

- over

- overall

- owner

- Paper

- paris

- particularly

- Passing

- performance

- performing

- person

- Personality

- planning

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- pleased

- politics

- Post

- Posts

- potential

- precursor

- present

- previous

- prof

- Professor

- prominent

- property

- protecting

- provided

- public

- purposes

- quality

- question

- Questioned

- quite

- Read

- Reality

- reasonable

- recent

- recently

- recognise

- recognition

- recommendations

- recommended

- reference

- referenced

- referred

- reflected

- reflection

- regarding

- regime

- regional

- register

- registered

- Registration

- registry

- regulations

- relation

- relaxed

- relevant

- relief

- remains

- Renowned

- requirement

- research

- respect

- REST

- restaurant

- Restaurants

- Room

- ruling

- s

- Safety

- same

- Sanctions

- says

- scientific

- scrutiny

- secretive

- Section

- see

- seemingly

- Selling

- serve

- serves

- service

- Services

- should

- showcasing

- significance

- similar

- Similarly

- simply

- since

- So

- Society

- somehow

- somewhat

- Source

- specific

- specifically

- specified

- standards

- Star

- Stars

- States

- Status

- Still

- such

- Suit

- supervises

- supply

- symbol

- taken

- technically

- technique

- Technology

- terms

- test

- than

- that

- The

- The Future

- the Law

- their

- There.

- they

- this

- those

- though?

- three

- Through

- Thus

- time

- TM

- to

- towards

- trade

- trademark

- trademark application

- trademarks

- traditional

- trusted

- two

- typical

- ultimate

- unauthorized

- unaware

- under

- underscore

- understand

- unfamiliar

- union

- unique

- university

- upcoming

- Update

- use

- used

- User

- uses

- Valuable

- various

- verify

- was

- Way..

- we

- Website

- welcome

- WELL

- were

- What

- when

- whether

- which

- WHO

- WISE

- with

- Word

- working

- would

- you

- zephyrnet