And why is the destination (a climate conference) and the passenger (a scientist) relevant at all? The emissions are the same even if the scientist is just on holiday, or if the passenger is a teacher or a civil servant. Is this just a psychological illusion, or is the value of the trip the fundamental part?

I have at different times have all of these ideas cross my mind, although without coming to a definite conclusion. It’s been a live issue for decades. It sailed into New Zealand in Shaun Hendy’s 2019 book #NoFly: Walking the Talk on Climate Change. Hendy’s year off from flying (he later started again) brought a personal flavour to the book and attracted a lot of publicity.

In a recent article, Should climate scientists fly? A case study of arguments at the system level, Jean Goodwin, a Professor of Communication at North Carolina State University, comes to my aid. She looks into the question not to try and answer it, or to assess the correctness of the different sides, but to understand how it has evolved as an argument. It’s been around so long, with so many people participating, that keen protagonists know all the arguments already and can anticipate which way things might go.

Here’s a recent entry into the genre, from well-known environmentalist George Monbiot, writing for the campaign Flight-Free UK:

I think your ability to change people’s minds is a function of your credibility, and your credibility is a function of the extent to which you live your values. You have to show people that you mean it. If people don’t think you mean it, and they don’t think you’re serious, they’re not going to follow you… what we need is structural and systemic change. However, we are much more likely to achieve that change if we live our values and show our commitment to the world we want to see. If the message we send out is that everyone else has got to change but not me, we’re far less likely to achieve that structural change.

Professor Goodwin analysed a sample of 100 opinion pieces and hundreds of thousands of tweets from 2010 to 2020, uncovering the main camps and their arguments. Ideas are passed around, picked up, and remixed. The whole thing is lumped together as “the hypocrisy argument”. She calls the three main groups the Skeptics, FlyLess, and SystemChange.

The Skeptics’ arguments are broken down into different types, which can be used individually or all at once:

- Don’t believe: “Why do any climate scientists still fly? It’s almost as if they don’t really believe that there’s a CO2 climate crisis.”

- Self-interest: “Yes all those scientist that will absolutely be out of job if there is no longer a climate crisis, but go ahead all the while those making all the money off this fly around in private jets have multiple mansion and continue to live like they don’t care but certainly want you to!”

- Hoax: “No-one in the activist camp actually believes that catastrophic planetary warming will result from unchecked CO2 emissions. This may seem a weird thing to say in view of the public pronouncements, but look at what they do…”

- Hypocrites: “That’s all the Big Climate Change Politicians, Scientists and actors do….. they all fly in big planes and drive big cars, biggest hypocrites on our planet.”

- Elite: “Celebs & scientists fly around the world to latest climate meetings but we must live in mud huts.”

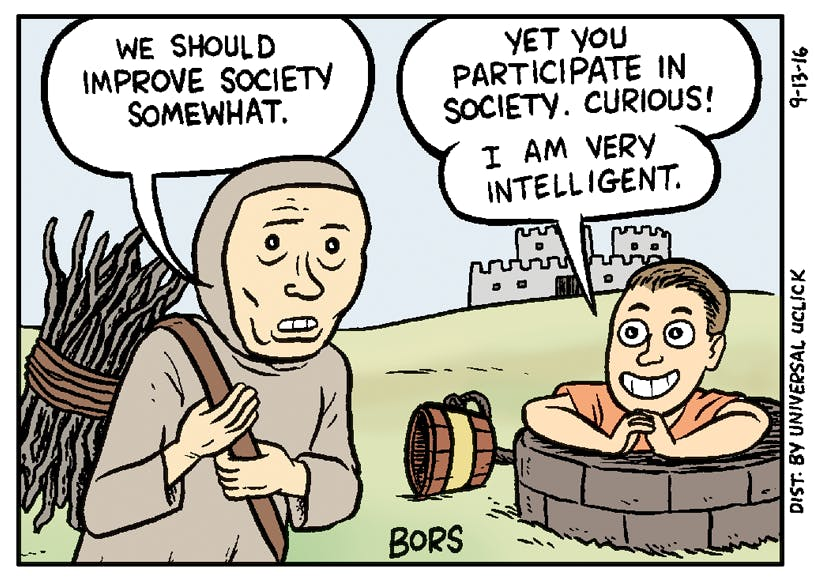

- Double standard: “Hypocrites always have an excuse why they should be excused from the rules that they wish to impose on the rest of society. If you actually thought carbon dioxide was a problem, you could always telecommute. Then again, your actions show that you don’t believe CO2 is a problem either.”

- Not credible: “You have a credibility problem when the climate scientists travel in private jets.”

- No emergency: “When ‘climate scientists’ like David Suzuki who own multiple homes and constantly fly all over the world start living as if we’re in any sort of danger I’ll start believing them.” “I will believe it’s a crisis, when the people telling me it’s a crisis, start acting like it’s a crisis.”

The skeptics deal with the apparent walk/talk inconsistency by arguing either that (a) the scientists do not believe that there is an emergency, or that they are bad people for either (b) not living up to their beliefs, (c) belonging to out-of-touch elites, as evidenced by their flying, or (d) their self-interest – or often, all of these at once.

In recent years, especially since the rise of Greta Thunberg and the Flygskam movement, the skeptics have been joined by a climate activists, making similar claims:

- “There are still “climate scientists” who fly to “climate conferences” seeking career-review/peer-review. What’s that? Oh sorry – Nearly all “climate scientists” propose that career (status) out-weighs the destruction of all careers & all states. Dear “climate scientist”, why not write down your thoughts on paper & then distribute them by post?… Otherwise, for you, I send this ancient curse – a plague on all your houses.”

The most common response has been to describe all of the skeptics’ arguments either as logical fallacies, or to counter that the skeptics themselves do not believe their arguments; that is, if the scientists did not fly, the skeptic would not suddenly recant:

- “Some climate scientists and campaigners don’t ever fly. But that’s hardly the point, stupid to say that you cannot participate in the system while attempting to reform the system. Your logical fallacy is a few of these including ad hominem & straw man https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com.”

- “If climate scientists fly the mitigation sceptics will call them hypocrites. If climate scientists do not fly the mitigation sceptics will call them activists. As always, the best advice is to ignore what the unreasonable will say.”

- “Zero of the climate movement’s enemies are arguing in good faith, if they ever were. That means anything the leaders do will be spun. If you’re not a hypocrite who flies you’re a judgmental hair- shirty preachy bore who doesn’t.”

There’s even a more sophisticated variant, that one philosopher called “tu quoque [hypocrisy] judo“: namely, the extreme difficulty of the scientist not flying the the conference itself illustrates the severity of the situation. (When Noam Chomsky was charged with hypocrisy for arguing that we should hold our investments to high ethical standards, while not following the advice himself, he replied, “What else can I do? Should I live in a cabin in Montana?”)

The second camp, FlyLess, emerged in the mid-2010s, and is exemplified by the websites FlyingLess.org (“Reducing academia’s carbon footprint” – the most recent post describes an overland conference trip from Boston to Mexico) and NoFlyClimateSci.org, founded by JPL scientist Peter Kalmus, who now has a significant profile as an academic activist. (Here’s his influential FlyLess article.) The FlyLess camp have accepted most of the skeptic’s arguments – all except the hoax/conspiracy ones, and that flying scientists are bad people – and developed them at length. They argue that flying less lends credibility, sends a costly signal, and can be a catalyst for system change.

- “I cannot be credible as a climate scientist if I don’t align my own behavior with what I’m saying one has to do. So this is not a per- sonal choice of stopping to fly because I don’t feel comfortable about it, but it’s a professional choice of reducing my emissions because I want to remain credible and I want to keep the trust of society.”

- “When we get on a plane, what we’re saying is: this flight is more important for me and for the climate than the damage that’s being caused by it. And there’s a— there’s a certain arrogance in that; that “We are a special elite that should be allowed to have higher carbon footprints than other people because what we are doing is so important.”

- “It is both arrogant and ineffective to point to the need for others to deliver major change if we are not willing to demonstrate how such changes can be viable within our own community. Leading by example may add not to the veracity of our research— but from experience it certainly adds to the credibility.”

- “Because there’s no carbon-free alternative to flying, its symbolic power becomes that much greater. By flying less or refusing to fly as scientists, we’re stating that the crisis is bad enough to merit moving away from business-as-usual practices to address it.”

- “I’ve realized that the main impact of reducing our emissions isn’t the emissions reduction itself: by modeling change, we tell a new story of what’s possible, shifting the culture and opening space for large-scale change.”

The final group, SystemChange, was exhibited recently in New Zealand, at a public event in which a climate scientist urged the audience not to feel guilty about not living the best possible life, because it’s system change that is needed. In other venues, it’s been put that the whole argument is fallacious, a distraction and a waste of time, and a tool of the fossil-fuel industry.

- “It’s a hill away from the main battle lines and they want us there rather than facing economic climate solutions head on which will take resolve and compromise from both sides of the political spectrum. Climate deniers would rather have us as far away from that as possible.”

- “There is an attempt being made by [the fossil fuel industry] to deflect attention away from finding policy solutions to global warming towards promoting individual behaviour changes that affect people’s diets, travel choices and other personal behaviour. This is a deflection campaign and a lot of well-meaning people have been taken in by it. We should also be aware how the forces of denial are exploiting the lifestyle change movement to get their supporters to argue with each other. It takes pressure off attempts to regulate the fossil fuel industry. This approach is a softer form of denial and in many ways it is more pernicious.”

In the final stage, which Professor Goodwin describes as a circular firing squad, the SystemChangers accuse FlyLess of being aligned with the Skeptics, while the Skeptics circulate SystemChange essays as evidence for their cause. She concludes:

[W]e count on controversies to form reasoned public opinion and produce public justifications on the most pressing issues of our communities… Participating in a controversy, arguers start to recognize how to argue in this controversy: they start to see who else is participating, what is in issue, what standpoints can be taken, who has the burden of proof, what evidence is available, what arguments can be made, what objections those arguments deserve.

After all that, I can hardly be expected to land a killer blow in this argument. For what it’s worth, the FlyLess argument on credibility does have some experimental support (although that’s probably not why its supporters believe in it). By now we are well into the next stage, which is to ask if climate scientists should be activists. Going to prison, now that really is costly signalling.

|

| PHOTO: Dwight Owens |

On 15 December 2022, Rose Abramoff and Peter Kalmus briefly interrupted an American Geophysical Union conference. AGU removed their research presentations from the meeting, banned them from participation, launched a misconduct inquiry, and complained to Abramoff’s employer, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Kalmus and Abramoff further claimed that AGU threatened to have them arrested if they returned to the meeting. Abramoff was subsequently fired by Oak Ridge. In January 2023, 1500 scientists signed an appeal to object to what happened to their colleagues.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.carbonnews.co.nz/story.asp?storyID=28092

- :has

- :is

- :not

- $UP

- 1

- 100

- 13

- 15%

- 2010

- 2019

- 2020

- 2022

- 2023

- a

- ability

- About

- about IT

- absolutely

- academic

- accepted

- Achieve

- acting

- actions

- Activist

- activists

- actors

- actually

- Ad

- add

- address

- Adds

- advice

- affect

- again

- ahead

- Aid

- align

- aligned

- All

- allowed

- already

- also

- alternative

- Although

- always

- American

- an

- Ancient

- and

- answer

- anticipate

- any

- anything

- apparent

- appeal

- approach

- ARE

- argue

- argument

- arguments

- around

- arrested

- article

- AS

- assess

- At

- attempting

- Attempts

- attention

- attracted

- audience

- available

- aware

- away

- Bad

- banned

- Battle

- BE

- because

- becomes

- been

- being

- beliefs

- believe

- believes

- believing

- BEST

- Big

- Biggest

- blow

- book

- boston

- both

- Both Sides

- briefly

- Broken

- brought

- burden

- but

- by

- call

- called

- Calls

- Camp

- Campaign

- CAN

- cannot

- carbon

- carbon dioxide

- care

- Career

- careers

- cars

- case

- case study

- Catalyst

- catastrophic

- Cause

- caused

- certain

- certainly

- change

- Changes

- charged

- choice

- choices

- claimed

- claims

- Climate

- Climate change

- climate crisis

- CO

- co2

- co2 emissions

- colleagues

- COM

- comes

- comfortable

- coming

- commitment

- Common

- Communication

- community

- compromise

- conclusion

- Conference

- constantly

- continue

- controversy

- costly

- could

- Counter

- Credibility

- credible

- crisis

- Cross

- Culture

- curse

- damage

- DANGER

- David

- deal

- decades

- December

- deliver

- demonstrate

- describe

- deserve

- destination

- developed

- DID

- different

- Difficulty

- distribute

- do

- does

- Doesn’t

- doing

- Dont

- down

- drive

- each

- Economic

- either

- elite

- else

- emerged

- emergency

- Emissions

- enemies

- enough

- entry

- especially

- Ether (ETH)

- ethical

- Even

- Event

- EVER

- everyone

- evidence

- evidenced

- evolved

- example

- Except

- expected

- experience

- extent

- extreme

- facing

- faith

- far

- feel

- few

- Files

- final

- finding

- firing

- flight

- flying

- follow

- following

- For

- Forces

- form

- fossil

- Fossil fuel

- Founded

- from

- Fuel

- function

- fundamental

- further

- George

- get

- Global

- global warming

- Go

- going

- good

- greater

- Group

- Group’s

- guilty

- happened

- Have

- he

- head

- High

- higher

- his

- hold

- Holiday

- Homes

- houses

- How

- How To

- However

- HTML

- http

- HTTPS

- Hundreds

- i

- I’LL

- ideas

- if

- Illusion

- illustrates

- image

- Impact

- important

- impose

- in

- In other

- Including

- individual

- Individually

- industry

- Influential

- inquiry

- interrupted

- into

- Investments

- issue

- issues

- IT

- ITS

- itself

- January

- Jets

- Job

- joined

- jpg

- jpl

- just

- Keen

- Keep

- Know

- laboratory

- Land

- large-scale

- later

- latest

- launched

- leaders

- leading

- Length

- less

- Life

- lifestyle

- like

- likely

- lines

- live

- living

- logical

- Long

- longer

- Look

- LOOKS

- Lot

- made

- Main

- major

- Making

- mansion

- many

- many people

- May..

- me

- mean

- means

- meeting

- meetings

- Merit

- message

- Mexico

- might

- mind

- minds

- mitigation

- modeling

- money

- more

- most

- movement

- moving

- much

- multiple

- must

- my

- namely

- National

- nearly

- Need

- needed

- New

- New Zealand

- news

- next

- no

- North

- north carolina

- now

- oak

- Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- object

- of

- off

- often

- oh

- on

- once

- ONE

- ones

- opening

- Opinion

- or

- Other

- Others

- otherwise

- our

- out

- over

- own

- Paper

- part

- participate

- participating

- participation

- passed

- People

- people’s

- personal

- Peter

- picked

- pieces

- Plague

- Planes

- planet

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Point

- policy

- political

- Politicians

- possible

- Post

- power

- practices

- Presentations

- pressing

- pressure

- prison

- private

- probably

- Problem

- produce

- professional

- Professor

- Profile

- promoting

- proof

- propose

- public

- public opinion

- publicity

- put

- question

- rather

- realized

- really

- recent

- recently

- recognize

- reducing

- reduction

- reform

- refusing

- Regulate

- relevant

- remain

- Removed

- research

- response

- REST

- result

- Rise

- ROSE

- rules

- same

- say

- saying

- Scientist

- scientists

- Second

- see

- seeking

- seem

- send

- sends

- serious

- she

- SHIFTING

- should

- show

- Sides

- Signal

- signed

- significant

- similar

- since

- situation

- Skeptics

- So

- Society

- Solutions

- sophisticated

- Space

- special

- Spectrum

- spun

- Stage

- standard

- standards

- start

- started

- State

- States

- stating

- Status

- Still

- stopping

- Story

- structural

- Study

- Subsequently

- such

- supporters

- symbolic

- system

- systemic

- Take

- taken

- takes

- Talk

- teacher

- tell

- than

- that

- The

- the world

- their

- Them

- themselves

- then

- There.

- These

- they

- thing

- things

- Think

- this

- those

- thought

- thousands

- three

- time

- times

- to

- together

- tool

- towards

- travel

- trip

- Trust

- try

- tweets

- types

- understand

- union

- university

- us

- used

- value

- Values

- Variant

- venues

- viable

- View

- W

- walking

- want

- was

- Waste

- Way..

- ways

- we

- WELL

- well-known

- were

- What

- What is

- when

- which

- while

- WHO

- whole

- why

- will

- willing

- with

- within

- without

- WordPress

- world

- worth

- would

- write

- writing

- year

- years

- you

- Your

- Zealand

- zephyrnet