After all these years and despite so many accomplishments, measures that save energy remain U.S. climate policy’s bastard child.

Even defenders of energy efficiency sell it short. The latest instance was last Friday’s NY Times column, Give Me Laundry Liberty or Give Me Death!, by the paper’s resident polemicist, the economist Paul Krugman.

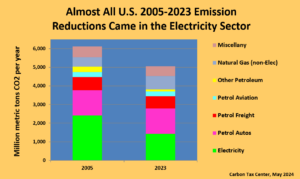

Electricity Savings’ top role in reducing electric-sector emissions is especially critical because no other sector (transport, industry, etc.) cut emissions more than marginally.

Krugman rightly savaged Congressional Republicans for contesting U.S. Energy Department efficiency standards for washing machines and other major energy-consuming appliances. His column reminds us that today’s G.O.P. never passes up an opportunity to force fossil fuels on the American public.

As Krugman noted, Republicans’ depiction of Democrats as enemies of freedom is exactly backwards: “Regulations ensuring that the appliances on offer are reasonably efficient reduce people’s cognitive burden — you might even say they increase our freedom,” by unshackling consumers from the task of weeding out inefficient (and expensive-to-run) appliances from efficient ones.

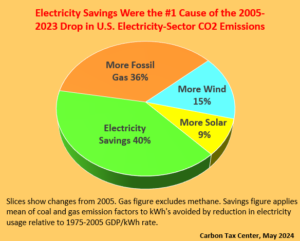

But consider what Nobel economics laureate Krugman left out: The only U.S. sector that has cut carbon emissions by more than token amounts since 2005 is electricity, furnishing a whopping 92 percent of the overall drop in emissions in 2023 since 2005. (See bar graph further below.) And energy savings, measured as kilowatt-hours that didn’t need to be generated because electricity savings curbed demand, accounted for 40 percent of electricity-sector carbon reductions — besting the 36 percent from power generators’ shift from coal to less-carbon-intensive fossil gas, and far surpassing the combined 24% share from growth in wind and solar electricity. (See pie-chart above. Details follow at end of post.)

Why are electricity savings undervalued?

Since 2005, the U.S. economy has grown by 40 percent in real (inflation-adjusted) terms. Yet over the same 18 years, U.S. electricity generation barely budged, rising just 5 percent. That is an immense change from mid-(20th)-century, when electricity usage typically grew each year by 6 or 7 percent, practically doubling every decade. This wrenching apart of electricity growth from economic growth has enabled the increased penetration of fossil gas-fired electricity and the rapid increase in wind and solar electricity to bite deeply into coal-fired power generation rather than simply add to it.

Yet energy savings are downgraded in energy and climate discourse. It’s not hard to see why.

First, energy saving is invisible. There are no ribbon-cuttings for energy-efficient buildings or appliances, no medals for low-energy lifestyles. Super-efficient houses or office buildings occasionally are singled out for praise, but what’s the visual — a low-electricity or gas bill? Or, worse, Jimmy Carter’s White House cardigan, which 1970s media held up for ridicule?

Second, saving energy lacks powerful lobbies. There’s no energy-saving counterpart to the American Gas Association, the American Wind Energy Association, the Solar Energy Industry Association, the National Coal Association, and certainly not the American Petroleum Institute, which was represented at the Mar-a-Lago dinner last week at which ex-president Trump pressed the fossil fuel industry for a billion dollars in campaign contributions. Only the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy and the Natural Resources Defense Council persistently advocate for energy effiicency, and they do so as tech experts and champions of the greater good rather than as arm-twisting lobbyists, and certainly not as bundlers of campaign cash.

Lime-green bars show CO2 emissions from electricity generation. The sole other sector with substantially lower 2023 emissions, “Other” Petroleum, shown in yellow, shrank due to natural gas’s increasing industrial-market share.

Energy efficiency and savings also suffer from a measurement problem. Implicit in measuring their climate contribution is a counterfactual: what would energy requirements and emissions have been without the energy savings?

For this post as well as predecessor posts in 2016 and 2020 I used as a baseline U.S. electricity generation if the 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had persisted. I think that was reasonable, but who’s to say? The avoided kWh’s I computed for the pie chart depend on a measuring convention that is subject to argument.

(Note that “offshoring” — the compositional shift of the U.S. economy toward services and away from manufacturing, with imports from China and other Asian countries furnishing the lost production — has also contributed to reducing the link between electricity and domestic economic activity; however, its numerical impact only accounts for a fraction of the flattening of U.S. electricity consumption over the paste two decades.)

Energy Efficiency’s Respect Deficit Is Consequential

Undervaluing energy efficiency means that energy-saving policy measures get short-changed. Efficiency standards for appliances, vehicles and buildings are insufficiently supported, enacted and enforced, leaving them vulnerable to being watered down or blocked altogether.

That’s the obvious part. More consequential is the cultural and political fallout. The short shrift accorded energy savings contributes to downplaying the demand side of energy and climate. This in turn has contributed to the unfortunate narrowcasting of climate campaigns to campaigns to block supply expansions. Measures that would curb consumption get disregarded, even though they are arguably more enduring and effective in curbing climate-damaging emissions than campaigns to halt drilling or pipelines, which largely relocate supply expansions elsewhere.

A major casualty of this narrowcasting is sidelining of carbon pricing as a serious policy contender. That’s not to say that the U.S. would necessarily have robust carbon pricing if energy savings were given their due. Rather, the marginalizing of energy savings and of carbon pricing are mutually reinforcing.

Part of the power of carbon taxing is that it operates on both the demand and supply sides of the fossil-fuel and emissions equation. (Another part is that carbon pricing complements virtually every other emissions-reducing policy or program.) Downgrading the demand aspect of our energy and climate miasma does a disservice to carbon pricing — and our climate.

Calculation Details

Calculations for this post were made in CTC’s carbon-tax model spreadsheet (2.2 MB downloadable Excel file). See Clean Electricity tab and Graphs tab. Pie-chart shares are derived by comparing 2023 and 2005 generation for solar (including distributed solar), wind and fossil gas and applying industry-average CO2 emission factors for coal and gas. Electricity-savings slice was computed by subtracting actual 2023 U.S. electricity generation from hypothetical 2023 generation if the average 1975-2005 ratio between electricity growth and GDP growth had continued through 2023, and then ascribing a per-kWh CO2 emission factor calculated as the mean of gas and coal CO2/kWh.

In crediting electricity with 92% of all 2005-2023 U.S. CO2 reductions (from fossil-fuel burning), I divided electricity-sector reductions of 983 million metric tons (“tonnes”) of CO2 by the total reduction of 1,064 million tonnes. However, the denominator is deflated by including “negative reductions” from passenger vehicles (14 million tonnes) and gas for industry (206). Even removing those sectors from the denominator, electricity accounted for 77% of total gross reductions (983 divided by 1,284). Note that these figures are shown in the Outcomes tab of CTC’s carbon-tax model.

<!–

–>

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.carbontax.org/blog/2024/05/12/will-energy-efficiency-ever-get-its-due/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- ][p

- $UP

- 1

- 14

- 2%

- 2005

- 2023

- 206

- 20th

- 35%

- 36

- 37

- 40

- 5

- 6

- 7

- a

- above

- accomplishments

- accounted

- Accounts

- activity

- actual

- add

- advocate

- All

- also

- altogether

- American

- amounts

- an

- and

- Another

- apart

- appliances

- Applying

- ARE

- arguably

- argument

- AS

- asian

- aspect

- Association

- At

- average

- avoided

- away

- backwards

- bar

- bars

- Baseline

- BE

- because

- been

- being

- below

- between

- Bill

- Billion

- Block

- blocked

- both

- buildings

- burden

- burning

- but

- by

- calculated

- Campaign

- Campaigns

- carbon

- carbon emissions

- Cash

- certainly

- Champions

- change

- Chart

- child

- China

- Climate

- co2

- co2 emissions

- Coal

- cognitive

- Column

- combined

- comparing

- complements

- computed

- Congressional

- consequential

- Consider

- Consumers

- consumption

- continued

- contributed

- contributes

- contribution

- contributions

- Convention

- Council

- Counterpart

- countries

- critical

- cultural

- curb

- curbing

- Cut

- dc

- decade

- decades

- deeply

- Defenders

- Defense

- DEFICIT

- Demand

- Democrats

- Department

- depend

- Derived

- description

- Despite

- details

- Dinner

- discourse

- distributed

- divided

- do

- does

- dollars

- Domestic

- doubling

- down

- Downgraded

- Drop

- due

- Economic

- Economic growth

- Economics

- Economist

- economy

- efficiency

- efficient

- electricity

- electricity consumption

- electricity usage

- elsewhere

- emission

- Emissions

- enabled

- end

- enduring

- enemies

- energy

- energy efficiency

- enforced

- ensuring

- equation

- especially

- etc

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- EVER

- Every

- exactly

- Excel

- experts

- factor

- factors

- fallout

- far

- Figures

- flattening

- follow

- For

- Force

- fossil

- Fossil fuel

- fossil fuels

- Freedom

- from

- Fuel

- fuels

- further

- GAS

- GDP

- gdp growth

- generated

- generation

- get

- Give

- given

- good

- graph

- greater

- grew

- gross

- grown

- Growth

- had

- Hard

- Have

- Held

- his

- House

- houses

- However

- HTML

- http

- HTTPS

- i

- if

- immense

- Impact

- imports

- in

- Including

- Increase

- increased

- increasing

- industry

- inefficient

- instance

- Institute

- into

- invisible

- IT

- ITS

- jimmy

- just

- Krugman

- lacks

- largely

- Last

- latest

- leaving

- left

- Liberty

- lifestyles

- LINK

- lobbyists

- lost

- lower

- Machines

- made

- major

- manufacturing

- many

- marginally

- max-width

- me

- mean

- means

- measured

- measurement

- measures

- measuring

- Medals

- Media

- metric

- might

- million

- model

- more

- mutually

- National

- Natural

- necessarily

- Need

- never

- no

- nobel

- note

- noted

- numerical

- NY

- obvious

- occasionally

- of

- offer

- Office

- on

- ones

- only

- operates

- Opportunity

- or

- Other

- our

- out

- over

- overall

- part

- passes

- Paul

- Paul Krugman

- penetration

- people’s

- percent

- persistently

- Petroleum

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- policy

- political

- Post

- Posts

- power

- powerful

- practically

- praise

- predecessor

- pricing

- Problem

- Production

- Program

- public

- rapid

- rather

- ratio

- real

- reasonable

- reduce

- reducing

- reduction

- reductions

- reinforcing

- remain

- removing

- Republicans

- Requirements

- Resources

- respect

- rising

- robust

- Role

- s

- same

- Save

- saving

- Savings

- say

- sector

- Sectors

- see

- sell

- serious

- Services

- Share

- Shares

- shift

- Short

- show

- shown

- side

- Sides

- simply

- since

- Slice

- So

- solar

- solar energy

- Spreadsheet

- standards

- subject

- substantially

- subtracting

- suffer

- supply

- Supported

- surpassing

- Task

- tech

- terms

- than

- that

- The

- The Economist

- their

- Them

- then

- There.

- These

- they

- Think

- this

- those

- though?

- Through

- times

- to

- today’s

- token

- tons

- top

- Total

- toward

- transport

- trump

- TURN

- two

- typically

- u.s.

- U.S. economy

- unfortunate

- us

- Usage

- used

- Vehicles

- virtually

- visual

- Vulnerable

- W3

- was

- washing

- week

- WELL

- were

- What

- when

- which

- white

- White House

- whopping

- why

- will

- wind

- wind energy

- with

- without

- worse

- would

- wrenching

- years

- yellow

- yet

- you

- zephyrnet